Closing the Loop: Building Systems That Learn and Adapt

How feedback loops drive growth, learning, and systems thinking in management.

Servus! I’m Nikolay and this is the third issue of the “From Dev to Lead” newsletter. I share practical tips for just-became-managers on how to survive and thrive in a new leadership role. To get issues like this every week, don’t forget to subscribe:

Hello there, fellow managers and aspiring leaders 👋

In the previous two issues, I focused on practical and actionable advice for managers. While useful for immediate application, a leader’s role isn’t just about personal efficiency. Managers are hired to take responsibility for specific areas and must establish systems that consistently deliver the desired outcomes.

Spoiler alert: throughout this newsletter, we’ll talk a lot about systems and the shift from reactive to proactive leadership.

New leaders often fall into the trap of jumping on every issue that arises, unintentionally becoming a bottleneck for their teams. This “hero” mentality likely played a significant role in earning you your promotion. But as you grow into a manager, you’ll quickly realize its limitations — it caps your potential impact.

True leadership lies in moving from focusing on individuals to thinking in terms of systems.

Today, we’re diving deeper into theory — exploring the foundational model that drives so much of what we do: feedback loops. Whether you realize it or not, you’ve already encountered, participated in, and even established many feedback loops. Some of them were intentional, others emerged naturally.

What is a feedback loop?

Let me explain. The theoretical definition is as follows:

Feedback occurs when outputs of a system are routed back as inputs as part of a chain of cause and effect that forms a circuit or loop.[1] The system can then be said to feed back into itself.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feedback

Admittedly, that sounds a bit too academic. Let’s break it down with some examples you, as a Computer Science professional, have likely encountered.

Feedback Loops in Agile Frameworks

Most readers here have probably worked with Agile methodologies.

Take SCRUM, for example — it’s packed with feedback loops:

Sprints: Feedback from the sprint review and retrospective is fed into the next sprint planning session as input.

Daily Scrums: A smaller, daily feedback loop where results from the previous day and the current state of work inform daily plans.

Feedback Loops in Continuous Integration (CI)

Here’s a purely technical example: the Continuous Integration process.

The input is the code.

CI systems execute linters, tests, or builds on the integrated version of the code (your branch merged with the main branch).

The output is the result of the CI process — it either passes (green) or requires fixes (red).

Based on the CI feedback, you decide whether to proceed or make changes.

Feedback Loops in Performance Reviews

A more human-oriented example would be performance reviews. You’ve likely participated in these during your career:

Goals or expectations are set for an individual.

The individual works toward these goals, using them as inputs for their performance.

At the end of the cycle, an evaluation occurs.

The results of the evaluation are then used as input for the next review cycle.

What’s common across these examples?

All feedback loops share three essential characteristics:

A loop: The process repeats itself continuously.

Assessment: There is a way to evaluate or inspect the results of the process.

Adaptation: The results of the assessment are fed back into the process as input for the next cycle.

Why are feedbacks important?

To understand the importance of feedback loops, let’s consider a counter-example.

Meet Bob, a Software Engineer at the imaginary Big-Tech company YooberBnB, renowned for its bitten-pear logo. Bob’s manager, Alice, values feedback and ensures they have bi-weekly 1:1s.

First Feedback Session

Alice: Hey Bob! I hope you enjoy the new job. I’ve spotted that you rarely write tests for your code. The product’s quality is crucial for our company and we believe that the code coverage helps us to ensure it. Please, start writing more tests for your code.

Bob: Sure! Thank you for the feedback!

So Bob has been doing something, and now he got feedback that he should write more tests. Duly noted — he immediately started to cover his code with tests up to 100%.

Second Feedback Session

Alice: “Hey Bob! It’s been three months since you joined YooberBnB, and we’re thrilled to have you here. You’re doing great! One thing I’d like to mention is about how you’ve been rolling out features. The last two releases went to 100% of users immediately. We have an established practice of using controllable feature switches to release functionality gradually—starting with 5% of users and scaling to 100% over two weeks. Here’s an article in our knowledge base about it: .”

Bob: “Oh! Sure, thank you for letting me know. I’ll start using feature switches for all future releases.”

What Happened?

In just a few weeks, Bob received two pieces of valuable feedback:

Write more tests.

Use feature switches for rolling out functionality.

Sounds great, right? But something critical is missing.

The Missing Piece

Alice never revisited Bob’s progress on writing tests. She gave initial input but never closed the loop by assessing whether Bob improved in this area. Bob doesn’t know if his efforts are meeting expectations or if the priority has shifted elsewhere.

Without this follow-up, Bob can only assume: “If it’s not mentioned anymore, I must be doing fine.” Does that help? A little, but it leaves room for doubt and misalignment.

The Risk of Open Feedback Loops

When feedback loops aren’t closed:

Managers may unintentionally pile on competing priorities, leaving employees confused about what’s most important.

Employees may deprioritize tasks that are never followed up on, potentially leading to underperformance in critical areas.

The Solution

To avoid this, both managers and employees should take proactive steps:

For managers: Revisit and assess previous feedback during follow-ups. Did the individual improve? Was the feedback implemented correctly?

For employees: If feedback isn’t explicitly addressed again, ask for it. “How am I doing on X?” can go a long way in clarifying priorities and expectations.

By closing the loop, you ensure clarity, alignment, and progress—key ingredients for a productive and trusting working relationship.

The same issue can occur not just on an individual level but also at the team or even company level.

Think about those quarterly meetings when your CEO presents the next set of BIG PROBLEMS WE NEED TO ADDRESS. Without revisiting or reflecting on the progress made on the previous goals, frustration can quickly build.

People start wondering: Was the work we did before even meaningful? Did it have any impact?

Unclosed feedback loops like these create uncertainty and disengagement, as individuals or teams are left questioning the value of their efforts.

Chances are, you’ve encountered plenty of examples of unclosed feedback loops throughout your career — or even in daily life. Share one in the comments — I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Useful Feedback Loop Model — PDCA

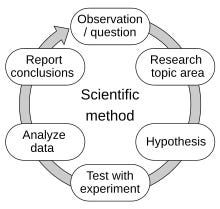

Let’s shift our focus back to theory. The cycle of planning, inspecting, and adapting has its roots in the scientific method — a framework for systematically learning and improving.

In the 20th century, this approach was formalized in management as the PDCA cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act).

The Four Steps of PDCA:

Plan — Define your actions for the next iteration using all available information. Make assumptions, form hypotheses, and set your objectives.

Do — Execute your plan.

Check (or “Study”) — Analyze the results by gathering data. Compare actual outcomes to your expected results. Were your hypotheses correct? Did reality align with your assumptions?

Act (or “Adjust”) — Use your findings to refine and improve the process. Revisit assumptions, draw conclusions, and incorporate lessons learned into the next planning stage.

This cycle’s power lies in its simplicity. It’s a framework for continuous improvement and serves as the foundation for many systems, including Kaizen, the Toyota Production System, marketing strategies, and general management.

The Check and Act steps are often overlooked. Why? Because reflecting on the past requires discipline, while moving forward feels more exciting and productive.

But skipping these steps comes at a cost. Without reflection and adjustment, you miss critical opportunities to learn. How often have you:

Planned something, executed it, and then ignored the results?

Realized that your assumptions were incorrect but didn’t change anything for the next iteration?

By skipping these steps, you stay static. And in today’s rapidly changing world, learning and adapting are essential for growth.

So, please, don’t forget to do the check and act parts at the end of each iteration. It is crucial.

What does it mean practically?

After setting a goal for yourself — set a cycle on which you assess the achieved results

After releasing a feature — check on it after a while, assess metrics, check if it really achieved the mission it was supposed to

Don’t leave feedback loops open — you are missing the important learning every time you do that.

Let me give you a bit of historical background. We have time, don’t we?

PDCA is sometimes referred to as PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act). And sometimes it is also called the Deming cycle, after the renowned management theorist W. Edwards Deming.

Interestingly, W.Edwards Deming himself attributed the cycle to Walter A. Shewhart, after a brilliant physicist and statistician Walter A. Shewhart, who is considered the godfather of statistical quality control. In fact, Deming referred to PDCA as the Shewhart Cycle in his writings.

Both Deming and Shewhart are pivotal figures in the evolution of management theory. Their work laid the groundwork for modern approaches to quality control, organizational learning, and continuous improvement.

Practical assignment for the next week

Throughout this article, we’ve explored feedback loops and how they’re used in both organizational and people management contexts. Now, let’s put theory into practice.

Step 1: Start with Yourself

Analyze your individual work. Identify areas where feedback loops might be missing. If you’ve followed my previous articles, you likely already have one in place: your weekly planning. What other areas could benefit from today’s learning?

For example:

Are you revisiting completed tasks to assess their outcomes?

Do you take time to reflect on projects before starting new ones?

Step 2: Move to Your Team

Evaluate your team’s current working process. Ask yourself:

How is the process structured?

Are there feedback loops to ensure learnings are incorporated into daily work?

Are any feedback loops broken or incomplete?

For instance:

Do your retrospectives lead to actionable changes?

Are recurring issues being addressed, or do they keep surfacing?

Step 3: Make a Hypothesis

Write down your observations and form a hypothesis on how to fix any gaps you’ve identified. Think through the validation process:

How will you measure success?

What metrics or outcomes will indicate that your action helped?

Step 4: Execute, Analyze, Adapt

Put your plan into action. Assess the results, adapt as needed, and iterate. The beauty of feedback loops is their continuous nature—each iteration brings you closer to improvement.

Bonus: Share your findings! Reflecting out loud (with your team or even in the comments) can lead to valuable insights and accountability.

With this, we close the feedback loop of this article — we’ve reflected on real-life scenarios, explored foundational theory, and discussed ways to apply it as actionable input. Feedback loops in action! Amazing work, and I hope this helps you take your leadership skills to the next level.

Book recommendations for curious readers

I believe that management is all about learning. Here are the books that influenced me the most in the past 10 years.

Peter M. Senge — The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization

Eliyahu M. Goldratt — The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement

They might not be immediately practical and applicable, however they help to create certain mental models that help to navigate in the complex world.

I hope you enjoyed today’s issue. It took me a bit longer to write as the topic is so important for me so I fell into the perfectionist trap. However, I think I covered what I wanted to say. Now it’s your turn.

Take notes. Close feedback loops. And above all — stay curious.

We’ve got this. Together 🚀

Thank you for reading. Don’t forget to subscribe to From Dev to Lead to stay tuned for future issues.